Wheat or weeds?

Sermon for the Eighth Sunday after Pentecost (July 23, 2023) at St. James’ Episcopal Church in Hyde Park, NY. A video of the entire worship service is available here.

What are we talking about? View the scripture readings and the Collect of the Day: Proper 11, Year A

Listen:

Like what you hear? You can subscribe to the podcast on Apple Podcasts or Spotify or Stitcher.

Then Jacob woke from his sleep and said, “Surely the Lord is in this place—and I did not know it!” And he was afraid, and said, “How awesome is this place! This is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven.” Genesis 28:16-17

Edited Transcript

May only truth be spoken here and only truth be heard. In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Please be seated.

So you'll have to forgive me if I've told this story before, but I love it so much that I'm going to tell it lots of times. So, buckle up <laugh>

It's about the monk Thomas Merton; about a vision that he had as a young man that changed the course of his life. And it happened on a very ordinary day, which, which he says himself, he was doing some errands for his monastic community in Louisville, Kentucky. It was your average busy day in a city. He was at the corner of Fourth and Walnut in Louisville, and you can perhaps just picture this regular day... People are running errands; people are bickering on the corner; somebody's walking with their baby in a carriage and there's cars honking at each other to get out of the way.

It's just an ordinary day; everybody's going about their business. You've got the good, the bad, and the ugly of people in close quarters.

But as Merton is walking down the street he's brought to a screeching halt, because suddenly, his heart is filled with love for all these ordinary people running errands and bickering and honking horns, yelling at each other, complaining. And he realizes... all of these people, and I too, we are all children of God. Every person I see on this ordinary street corner is infinitely beloved of God. He sees, in every person, a point of light in their heart. And he says, if only we could see this light every day, this light in each one's heart—whether it's the person honking their horn, the person being rude to the shopkeeper, the patient shopkeeper, the parent with their stroller, the baby in the stroller—if we could see the points of light in each one's heart—

Then the world would be so bright that there would be no darkness. "Darkness is not dark to you, O God," says Psalm 139. "To you, darkness and light are both alike."

Merton had this vision and then it just as quickly passed, but he never forgot it.

He got to see, really see, and really feel that every human being is part of the family of God, the good, the bad, the ugly, the sinner and the saint, the annoying ones and the fun ones, the ones who are right and the ones who are wrong... He said, if we could see that, and "there is no program for this seeing"—you can't train yourself to see it, he said, it's just a gift that God will give you.

But if you could see it, then we would know, that "the gate of heaven is everywhere." Everywhere: On the corner of Fourth and Walnut; in the narthex of this church. Everywhere: where there's a migrant boat sinking into the Mediterranean sea; where there's a hungry person on the corner: All of them are shining with the light of God.

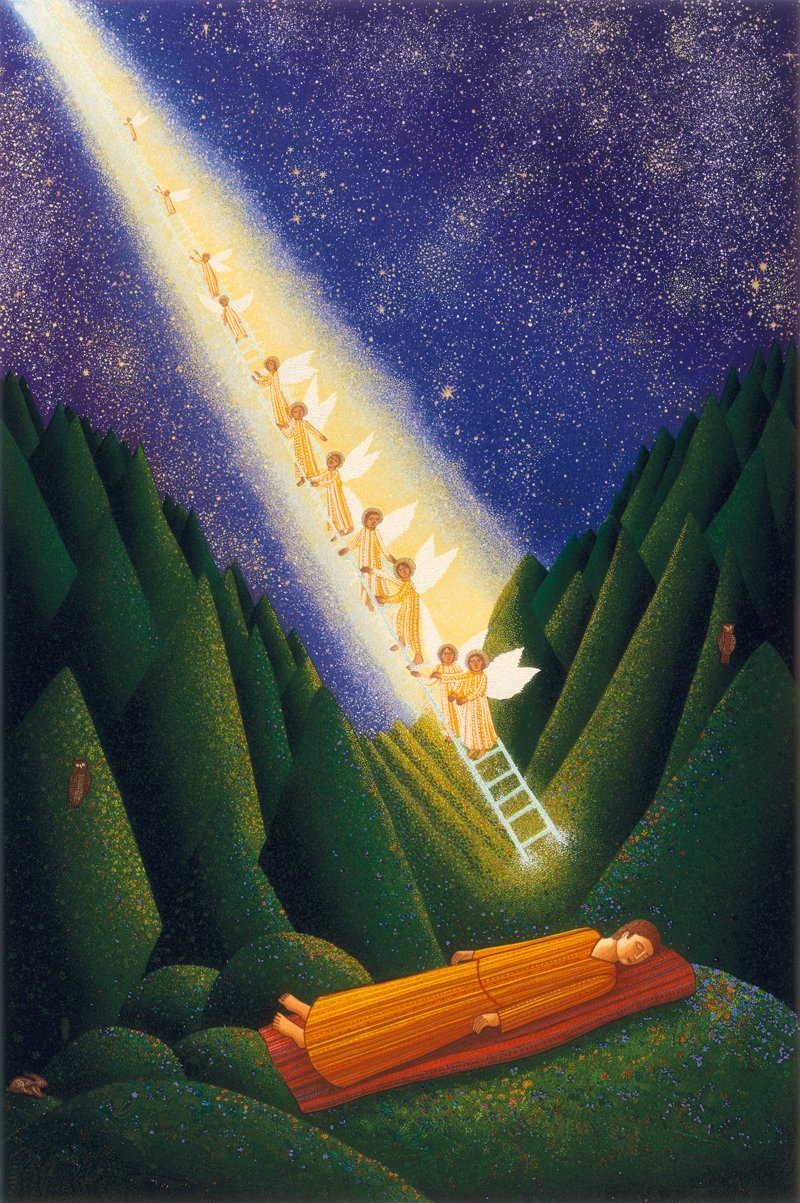

This is what Jacob knew from his dream. When he woke up in his dream, he saw the angels of God on a ladder, ascending and descending from heaven. In his dream, God stands beside him, watching the angels, and God says, "you will be blessed. You will be a blessing. You will bear fruit: the promise that I made to your father Isaac, the promise that I made to your grandfather Abraham, that promise is for you, too. And of course Jacob didn't do a whole lot to deserve this promise, but God met him anyway, and said, this promise is for you!

When Jacob wakes up, he says, "God was in this place, and I didn't know it." "This is the gate of heaven!" he says.

And what Merton later realized is that the gate of heaven is everywhere. If only we could see.

Now the story Jesus tells today is about weeds and wheat. It seems natural to say, okay, if we want to help build the kingdom of God, if we want to make this world more like God's dream, then doesn't it make sense to root out all the evil, all the wrong, all the injustice? And then on to the more petty stuff: all the little things, my little faults and foibles, and then especially the faults and foibles of the person next to me. It would be great if we could weed those out too, right?

Isn't that how we produce fruit? Isn't that how we bring the kingdom of God a little bit closer? By getting rid of the stuff that God clearly doesn't want in the field?

In Jesus' parable, there are fruiting grains in the field, and then some bad guy comes and puts weeds in there too. And so the people who are in charge of tending to the field day to day can see that the obvious solution is to pull those weeds out before they choke the good stuff, before they take over.

But the owner of the field says, this isn't the time. Let it lie. Because in fact, if you start pulling those weeds out now.... Have you ever planted little tiny seedlings, and then you find little tiny weeds growing alongside them? If you start pulling out the weeks, all the roots are tangled together. So you pull the weeds, but everything comes out together.

And also, at the beginning, it can be really hard to tell what's a weed and what's a seed; what's a desireable plant, and what's not.

And so, instead of doing the thing we think we ought to do—which is to weed out what's not good, weed out the evil, weed out what's not needed so that the good can flourish—instead, in this story, Jesus is offering an alternative to us, which is:

Take a deep breath and wait and see.

I don't really want to do that. I would much rather improve myself and improve the people around me, so that we can bring on the good stuff faster. And it's easy to joke about, when we're talking about like the petty little things that make up most of our life. But this pause is even harder to bear when we are talking about the injustice we see in the world, when we're talking about what clearly seems evil in the world. When we talk about people that are being hurt in the world. How can it be right to let these things grow? How can it be right to let the beauty and the good grow side by side with the unjust and the wrong?

To answer this question, let's go back to Jacob, our great, great, great, great, great, great, great grandfather in the life of faith, in life with God. I want us to think about Abraham, Sarah, Hagar, Ishmael, Isaac, Rebecca, Jacob, and Esau.

If this family, chosen by God, was a field, which one of them is the good seed? And which are the ones who are obviously behaving terribly and should be plucked out?

Is it Jacob, who tricked his brother out of his birthright by withholding stew when he was hungry? Is it Rebecca, the mother who told her favorite son to dress up as her other son, so that he could trick his blind father out of a blessing? Is it Abraham, who was willing to sacrifice his son on the altar?

Oh, don't forget that Isaac and Rebecca, just like Isaac's parents Abraham and Sarah, had this little thing they loved to do, which appears repeatedly in Genesis, where they would go into a foreign land, and the husband would pretend that his wife was really his sister... And the king of that land would bring what he thought was a single woman into his house, and God would send plagues on the king until they figured it out, and loaded the couple up with gifts in hopes of avoiding further supernatural punishment...

The point is: what an extraordinary family. Our ancestors in faith are an unending source of entertainment, and also grief.

Which of these ancestors deserves to grow; which of them deserves to be made a blessing? Which member or members of this family are the weeds, and which are the wheat?

That's part of what Jesus is teaching us in this parable. God doesn't bless Abraham or Isaac or Jacob because of how excellent and moral and good they have been, because of how much they've deserved a blessing.

God blesses them because God said that God would bless them.

This is the same God who, not so very many generations earlier, was so tired of humanity's behavior that God decided God would send a flood to wipe them all away and start over: Because I planted this field of wheat, and now, growing in it, is all this family dysfunction and people pretending their wives are their sisters, and people willing to sacrifice their sons and people tricking one another out of their birthright.

But God has chosen this family and made a commitment, and God is faithful to humanity now—not conditionally—but no matter what.

God is faithful to me, and to the person next to me, whether we are weed or wheat. And really, if each of us were a field, we would be weeds and wheat with our roots so intertwined that there's no possibility of plucking out what's undesirable and leaving only the good.

As individuals and as communities, we are weeds, and wheat. And yet somehow God is faithful.

Do you know why Jacob is in the desert, where he has his dream? Because he's running away from his brother Esau, who wants to kill him.

Jacob dressed up as his brother, who was a hairy guy. So Jacob puts goat skin on his hands and wears his brother's clothes so that he can trick their blind father into blessing him, Jacob, even though the father intended to bless Esau. And, not surprisingly, his brother wants revenge. So Jacob is running into the wilderness, on the pretext of looking for a wife, to get away.

Jacob is not looking good in this story. And yet in the middle of all of Jacob's "weediness," God meets him there.

God meets him there, and shows him this vision of heaven and earth touching, angels ascending and descending—which is what happens at Eucharist, at Baptism. Our sacraments are about that affirmation of the truth that heaven and earth are touching—no matter who we are as people, individuals, communities, nations, as a world.

God is meeting us right here, as we are. On that ordinary street corner or in this ordinary church.

Even the person with whom we most disagree, even the person who is the most in the wrong, even if that's us, has a point of light that is God, and God's spirit dwelling within them.

There's no guaranteed program to see this, but if we could, we would see that even in the weediest field, there is the gate of heaven.

The gate of heaven is everywhere. And there is no growing living thing, whether weed or wheat, that is not touched by God and to whom God is not still faithful.

If we could see, then we would know that heaven and earth are touching.

And when God shows us those glimpses, that is where we hope: not because of our perfection, and not because we've been able to root out every evil or injustice, but because God has established a link in Jesus that can't be broken: not over time, not over space, where the angels of God ascend and descend and where, in every time and every place the gate of heaven is open. Amen.